5. Sources Chelmsford Cathedral is familiar territory for me, being the Cathedral where I was ordained as a deacon. Since then I have attended many Diocesan services, organised exhibitions and events, and have also spoken in the Cathedral on several occasions. It was also where I began my sabbatical art pilgrimage, when attending a service to celebrate the centenary of Chelmsford Diocese. Despite its familiarity, this Cathedral continues to surprise and entrance. Examining the sources and connections of its art only deepens the encounter.

The dedications of the Cathedral are to St Mary the Virgin, St Peter, and St Cedd. These dedications feature in much of the work commissioned. Cedd is the subject of

Mark Cazalet's engraved glass window in St Cedd's Chapel, commissioned for the centenary of Cathedral and Diocese. He also has a bit part in Cazalet's

Tree of Life located in a blank window space within the North Transept and mimicking the mullions and tracery of the original window. The image of a single tree has been a recurring theme in Cazalet's work, influenced by the sense of place found within the English Romantic landscape tradition. Cazalet's image of an Essex oak as

Tree of Life uses symmetry to explore the theme with one side showing the Tree dying back and the other bursting into life.

Cazalet and

Peter Eugene Ball were two names that I knew I would encounter again and again on my pilgrimage as they have been among those contemporary artists most frequently commissioned by the Church in the UK. Ball is a sculptor who works with found objects, predominantly wood, which he then embellishes with beaten metals such as gold leaf. His Christ in Glory located high above the Nave with its outstretched arms is a welcoming image. On a smaller scale and possessed of a still serenity are his cross and candlesticks for the Mildmay Chapel and his

Mother and Child in St Cedd's Chapel.

Earlier commissions were no less significant however.

Georg Ehrlich's sculpture

The Bombed Child in St Peter's Chapel and his relief

Christ the Healer are particularly affecting. The commissioning by the Church in the UK of work from artists who were refugees from the Nazi's would prove to be another recurring feature of my pilgrimage. Former Dean, The Very Revd Peter Judd, said of

The Bombed Child: ‘A mother holds her dead child across her lap, and the suffering and dignity of her bearing don’t need any words to describe them – that is communicated to anyone who looks at her.’

[i]John Hutton's Great West Screen at Coventry Cathedral is one of the most notable works of religious art of the 20th century in Britain. Here his etched window is an image of St Peter. Elsewhere in the Diocese Hutton's work can also be found at St Erkenwald's Barking and St George's Barkingside. The work of

Thomas Bayliss Huxley-Jones also features elsewhere within the Diocese. His Woman of Samaria at St Peter's Aldborough Hatch and the Christ figure above the South Porch of St. Martin Le Tours church, Basildon are both fibreglass figures. At the Cathedral, Huxley-Jones' work includes a

Christus in St Cedd's Chapel, a carving of St Peter on the south-east corner of the South Transept and 16 stone carvings representing the history and concerns of Essex, Chelmsford, and the Church.

The number and variety of commissions which feature within this Cathedral mean that even in a packed service, such as that celebrating the centenary, when each worshipper will only see from their specific place within the space a very small proportion of the artworks within the building, they will, nevertheless, be able to view something of significance and depth to enhance their experience of worship. Among the range and variety of works to be seen - which include, among others, work in bronze, glass, steel, textiles, and wood - are finally a significant collection of contemporary icons followed the dedications of the Cathedral, with the addition of Jesus. These were created by orthodox nuns from the

Community of St John the Baptist at Tolleshunt Knights in Essex. The Cathedral’s commissions have therefore also served to support the revival of traditional iconography which as the iconographer

Aidan Hart has argued is a characteristic of twentieth century church commissions.

All this indicates the care with which the many commissions here at Chelmsford have been undertaken and realised, with commissions often relating to specific sources found in the life or heritage of the Cathedral. As is often the case, specific individuals have played a key role in taking these commissions forward appropriately and sensitively. At Chelmsford that role was particularly played by Peter Judd, who in an earlier role as the Vicar of

St Mary’s Iffley, oversaw the installation of a Nativity window by

John Piper which was later counter-balanced by

Roger Wagner’s

The Flowering Tree. A similar concern with balance can be seen at Chelmsford, in particular in the decision to commission Cazalet’s engraved St Cedd window in St Cedd’s Chapel as a counter-balance to Hutton’s engraved St Peter window in St Peter’s Chapel.

Commissioning several works from the same artists and positioning these at different locations within the space also indicates an awareness of the differing ways in which visitors and worshippers use and respond to the space. Artworks integrated within the life and architecture of a church are not viewed in the same way as works within the white cube of a gallery space and this needs to be understood and handled with sensitivity during the commissioning process. The result, as here, can be a sense of overall integrity and harmony within a space which holds great variety and diversity. Where this occurs, the whole and its constituent parts image something of the Trinitarian belief – the one and the many - which is at the heart of Christianity.

Slowing down to sustain silent looking by immersing ourselves in the world created by the work will in time also lead us outwards once again to consider the relationship of the work to the artist and the world in which s/he brought it to birth. There are four facets of any artwork – the artwork itself as an artefact, the ideas and influences of the artist, the relationship that the artwork has with its historical and art historical context, and our own response and that of others to the artwork. Each of these can shape our overall response to the artwork, often in ways that we don’t expect or realize.

It is particularly helpful for contemplation to consider the sources - ideas and influences - of the artist, as, when God created human beings, we were said to be made in his image. As a result, something of the maker shows up in the thing which has been made. By knowing something about the artist, we may be able to see and contemplate more in the artwork than we otherwise would. St Paul says the same thing about God in his letter to the Romans when he says that ever since the creation of the world God’s eternal power and divine nature, invisible though they are, have been understood and seen through the things he has made (Romans 1.19—20).

Corita Kent begins her discussion of the value in knowing sources with a dictionary definition:

‘SOURCE: from the Latin surgere, “to spring up, to lift.” The beginning of a stream of water or the like; a spring, a fountain. The origin; the first or ultimate cause. A person, book, or document that supplies information. A source is a point of departure.’

[ii] For the artist everything and anything can be a source. Sources, Kent suggests, free us ‘to depart from something rather than from nothing or everything.’

[iii] This ‘relieves us of thinking we have to make something new or great’ by enabling us to work with what is at hand while seeking to use the source as a reference and not as something to duplicate.

Kent encourages artists to do two important things in relation to their sources. The first is to ‘use and build on the ideas of others.’ She notes that

T. S. Eliot says that a minor poet borrows, a great poet steals. ‘Borrowing implies that the source really keeps possession,’ while stealing ‘implies that the source has become the property of the thief.’

[iv] However, when we know we are building on the ideas of others, ‘it is good to take responsibility and say thank you for the use of the material.’ So, when you can, ‘salute your source, otherwise, without heart or conscience, the work might become plagiarism.’

[v] Our primary sources are the Word of God; principally Jesus, but also creation and the Bible.

Richard Carter commends holy listening, attentiveness to the Word made flesh as essential to a rule of life. He writes: ‘You will return to the same stories again and again always with new questions as you bring your life to the Scriptures and the Scriptures to life’:

‘Like Jesus, we need to listen, to question, to discover for ourselves and to return to the Scriptures again and again. We seek openness to the Word of God, spaciousness in us so that we allow the Scriptures to dwell in us and ourselves to dwell in Scripture. The Word made flesh. An obedience to God’s Spirit within us.’

[vi] Our sources are our points of departure; the place from which prayer or contemplation begins. We need a starting point for any journey, whether geographical or within the mind or heart. In the same way that Kent encourages artists to see everything and anything as a potential source, so the mystics prompt us to see that God works in and through the ordinary and every day, through the people and things around us. As

Daniel Siedell noted in the quote that sparked this book and enquiry, we therefore need to be paying attention and looking out for signs of his activity and presence. We need to be listening for the Holy Spirit to prompt us to look at some ordinary thing or ordinary person in order to see the face of God.

In the film

American Beauty, Ricky shows Jane a blurry video of a plastic bag blowing in the wind among autumn leaves. As they watch he explains that ‘this bag was, like, dancing with me. Like a little kid begging me to play with it. . . . And that’s the day I knew there was this entire life behind things, and this incredibly benevolent force, that wanted me to know there was no reason to be afraid. Ever.’ ‘Sometimes,’ he says, ‘there’s so much beauty in the world I feel like I can’t take it, like my heart’s going to cave in.’

[vii] To encounter God as that incredibly benevolent force that wants us to know that there is no reason to ever feel afraid, we need to pay attention to the beauty of the ordinary, overlooked things in life, like a plastic bag being blown by the wind. As

Saint Augustine said, ‘How many common things are trodden underfoot which, if examined carefully, awaken our astonishment.’

[viii] Jean Pierre de Caussade was a French Jesuit priest and writer known for Abandonment to Divine Providence and his work with Nuns of the Visitation in Nancy, France. De Caussade coined a phrase to describe what we have just been talking about. He called it 'The Sacrament of the Present Moment,' which:

‘refers to God's coming to us at each moment, as really and truly as God is present in the Sacraments of the Church ... In other words, in each moment of our lives God is present under the signs of what is ordinary and mundane. Only those who are spiritually aware and alert discover God's presence in what can seem like nothing at all. This keeps us from thinking and behaving as if only grand deeds and high flown sentiments are 'Godly'. Rather, God is equally present in the small things of life as in the great. God is there in life's daily routine, in dull moments, in dry prayers ... There is nothing that happens to us in which God cannot be found. What we need are the eyes of faith to discern God as God comes at each moment - truly present, truly living, truly attentive to the needs of each one.’

[ix] Similarly,

Simon Small has written that: ‘To pay profound attention to reality is prayer, because to enter the depths of this moment is to encounter God. There is always only now. It is the only place that God can be found.’ So, contemplative prayer is ‘the art of paying attention to what is.’

[x]As a member of the Carmelite Order in France during the 17th Century,

Brother Lawrence spent most of his life in the kitchen or mending shoes, but became a great spiritual guide. He saw God in the mundane tasks he carried out in the priory kitchen. Daily life for him was an ongoing conversation with God. He wrote, ‘we need only to recognize God intimately present with us, to address ourselves to Him every moment.’

As a result, ‘The time of action does not differ from that of prayer. I possess God as peacefully in the bustle of my kitchen, where sometimes several people are asking me for different things at the same time, as I do upon my knees before the Holy Sacrament.’

‘It is not needful to have great things to do. I turn my little omelette in the pan for the love of God. When it is finished, if I have nothing to do, I prostrate myself on the ground and worship my God, who gave me the grace to make it, after which I arise happier than a king. When I can do nothing else, it is enough to have picked up a straw for the love of God.’

‘We ought not to be weary of doing little things for the love of God, who regards not the greatness of the work, but the love with which it is performed.’

[xi] This sort of spirituality - the sense of the presence of God in all things, and the possibility of honouring God in every action, as the source of spirituality - is also found in our hymn books. We sing:

‘Teach me, my God and King,

In all things thee to see,

And what I do in any thing,

To do it as for thee:’

George Herbert’s hymn, originally a poem called ‘The Elixir,’ ends with these words:

‘A servant with this clause

Makes drudgery divine:

Who sweeps a room, as for thy laws,

Makes that and the action fine.

This is the famous stone

That turneth all to gold:

For that which God doth touch and own

Cannot for less be told.’

[xii] If we practise the presence of God in the sacrament of the present moment, as Brother Lawrence and Jean Pierre de Caussade teach us, then we will become able to see signs of God’s activity and presence all around us and this will become the source of our prayer and creativity.

In the same way, all art is created in a particular time and place – its present moment - being in relationship with that contemporary context whilst also relating in some way to its art historical context. One Lent I was involved in the first showing of a digital installation by

Michael Takeo Magruder called

Lamentation for the Forsaken. In this piece the artist evokes the memory of Syrians who have passed away in the present conflict by weaving their names and images into a contemporary Shroud of Turin. That installation couldn’t be understood without reference to the then current refugee crisis or to past depictions of Christ, especially the Turin Shroud itself. We understand each other and artworks more by observing how we react and respond to events around us and to our histories and heritage. The artwork also became a focus for awareness and prayer as we explored the sources that had led to its creation. This is also why contemplation of the sources which inspired the artist has value, both for us and for others with whom we share our reflections.

ExploreView

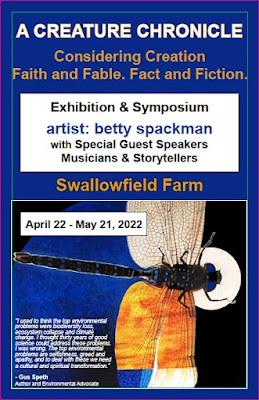

https://imago-arts.org/betty-spackman-a-creature-chronicle/ and https://static1.squarespace.com/static/59b04904e5dd5b7fad3953e1/t/5e5d785310cf69734cf6d2a2/1583183958600/CC+PROGRAM+BOOKLET.pdf to see a project using its sources as the basis for its form.

Betty Spackman has a background in animation and, having taught visual storytelling for many years, has underpinned her interest in narrative as an important part of a work entitled

A Creature Chronicle. This installation combines the stories of both science and religion using well known art works as mediators and commentators to explore ethical concerns in both fields regarding transgenics and the development of post humanism. These stories and images are her sources. Presenting itself as a non-linear multi-layered storyboard the work functions as a catalyst for dialogue - a physical presence to be walked around and sat inside, with visual stories to be ‘read’ or discovered, contemplated, and discussed.

The basic structure of

A Creature Chronicle is a 24ft in diameter circle of panels painted on both interior and exterior surfaces. As an architectural space it references a fire pit, a cave, a chapel, a hut. It is a place of contemplation and conversation. The circle is a universal symbol appearing in all world religions and science and is used in this work as a design element loaded with multiple complex symbolisms that repeat and spin their overlapping meanings.

Spackman’s intent was that combining the narratives of faith and art and science, even as fragmented visual quotes (these being her sources), would be a way to break the linear lines of ‘telling’ and give space for the various narratives to connect, conflate even. Her hope was that collaging the image stories from faith and art and science might help others see how they may have some common ground and allow conversations to be more than binary and argumentative. She wanted to invite contemplation and conversation by being hospitable in bringing many different voices (or sources) together on equal terms. The collage and the circular, double sided ‘storyboard’ encouraged this equitability as one can ‘read’ from any direction in any order even though there is a rough chronology implied.

[xiii]Spackman has said: ‘I place the Superman logo beside a human uterus and the story of Superman and the story of human birth create meaning by being in proximity. Why do we want to be super, to be heroes? Why is the goal of transhumanism to augment us, to rebirth us into super humans? What is the role of the woman, of reproduction? Who decides how birth of a new being will happen? And the plot thickens and becomes more and more complex. If I say ‘uterus’ one of my friends will tell her story of having a hysterectomy and someone else will tell a story of an abortion and someone else will tell a story of cloning and so on. The stories are always multiple and complex. Some are true and beautiful and some are not.’

[xiv]A Creature Chronicle is about ‘how we tell our stories of the origin and evolution of life’ but is also a chronicle of Spackman’s ‘own process of discerning ways of seeing and believing through the kaleidoscope of images’ she has collected over the course of her life:

‘I collage the fragments of my wonder and my wandering with various selected symbols from faith and science – ‘glued’ together and in part interpreted by fragments of well-known artworks. They are a disclosure of my curiosity as well as my convictions, simultaneously constant and evolving. It is a very personal story in that regard and I am cognizant of my choices being filtered through my own limited experiences, and therefore, aware of their limitations …

I believe … that there is a source and significance to life, although as an artist and writer I know how complicated it is to try and use either words or images to express or explain what we think or experience or discover. The scientist and theologian both try to define what life is about, the artist perhaps stands between them, sometimes mediating, sometimes ignoring them both. None of us speaks very clearly. Yet sometimes, through the babble of our various languages and our inadequate symbolic diagrams, we manage to communicate something – even if it is just our questions. But in comparing notes we might find there is more to be in awe of than to argue about. I hope so.’

[xv]In this way, and, perhaps, more than at any other time in human history, Spackman believes, the arts can play the role of mediators, interpreters, and inquisitors – as well as comforters, and healers - providing places of hospitality and humility where the big questions of life can be examined freely and safely. This is her achievement in

A Creature Chronicle, made possible by collaging together a multiplicity of sources from the arts, religion and science.

Wonderings I wonder what the sources for your personality, beliefs and practices are. I wonder what it is or who it is that has formed you.

I wonder how you discovered the sources for the personality, beliefs and practices of someone significant for you.

I wonder what your favourite piece of art - dance, drama, film, music, visual art etc. - is. I wonder how much you know about its creation, how you came by that information and how it enhances your appreciation.

Prayer God of pilgrimage, lead me on a journey back in time to know myself more deeply through the people, places, experiences and ideas that have shaped me. As I map my pilgrimage, open my eyes to the ways you have created, led and formed me. Amen.

Spiritual exercise Draw a map of the places that have formed you (however you wish to define formation). If there is the opportunity revisit those places and pray there about all that happened to you in that place. However, as will be the case for most of us, if that is not possible make that pilgrimage of prayer in your mind using anything that you have to hand to remind you of those places.

Art activity See what interests you about sources from the information available in the National Gallery’s Art & Religion strand -

https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/research/about-research/art-and-religion.

Read this interview with Betty Spackman -

https://www.artlyst.com/features/betty-spackman-posthumanism-debates-interview-revd-jonathan-evens/.

Click

here for the other parts of

'Seeing is Receiving'. See also

'And a little child shall lead them' which explores similar themes.

[i] https://www.marconi-veterans.com/?p=807 [ii] C. Kent & J. Steward, Learning by Heart, Allworth Press, 2008, p.40

[iii] C. Kent & J. Steward, Learning by Heart, Allworth Press, 2008, p.47

[iv] C. Kent & J. Steward, Learning by Heart, Allworth Press, 2008, p.51

[v] C. Kent & J. Steward, Learning by Heart, Allworth Press, 2008, p.58

[vi] R. Carter, The City is my Monastery: A contemporary Rule of Life, Canterbury Press Norwich, 2019, p.98

[vii] A. Ball, American Beauty screenplay, 1999 -

http://www.screenplaydb.com/film/scripts/American%20Beauty.pdf[viii] St Augustine, ‘Letter 137’, Selected Letters translated by J. G. Cunningham, Logos Virtual Library -

https://www.logoslibrary.org/augustine/letters/137.html [ix] Elizabeth Ruth Obbard, Life in God's NOW, New City, 2012

[x] Simon Small, From the Bottom of the Pond, O Books, 2007

[xi] Brother Lawrence, The Practice of the Presence of God, Hodder & Stoughton, 2009

[xii] G. Herbert, ‘The Elixir’ in The Temple, Penguin Classics, 2017

[xiii] B. Spackman, A Creature Chronicle. Considering Creation. Faith and Fable. Fact and Fiction.,Piquant, 2019

[xiv] https://www.artlyst.com/features/betty-spackman-posthumanism-debates-interview-revd-jonathan-evens/ [xv] B. Spackman, A Creature Chronicle. Considering Creation. Faith and Fable. Fact and Fiction.,Piquant, 2019

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------